Tomorrow, Sunday, June 12, my garden will be opened for its second tour of the season: the Victorian Flatbush House (and Garden!) Tour, to benefit the Flatbush Development Corporation (FDC). Earlier this week, I wrote about the transformation of the garden over the six past years, since we bought our home. Today, I’m providing details about one part of that transformation, one which is easy to replicate on a small scale, even in a tree bed or on a balcony.

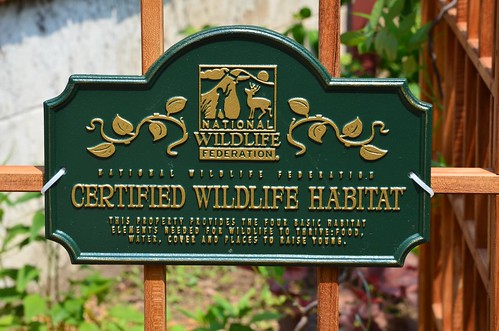

After readying my backyard native plant garden for its debut tour for NYC Wildflower Week in May, I decided to complete the requirements to register my garden as a Certified Wildlife Habitat (#141,173) with the National Wildlife Federation. With over 80 species of native plants, I easily met three of the four requirements: shelter, food, and places to raise young. All I lacked was water, a requirement satisfied by placing some birdbaths and a terra-cotta cistern.

On Friday, May 27, I mounted the plaque on the entrance arbor.

The morning after I put out this welcome mat, I saw butterflies visiting a vine in the garden. I was puzzled, since the plant wasn’t blooming yet. Closer observation revealed that they were laying eggs on the vine.

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, ovipositing on Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine

At first, I thought they were Papilo troilus, Spicebush Swallowtail, a species I’ve encountered before. But one of my tweeps, Marielle Anzelone, id’d it as Pipevine Swallowtail, a lifer butterfly for me. Upon researching the species, I was somewhat relieved to learn my confusion has some scientific basis: both the Spicebush and Pipevine Swallowtails, along with several other species, are members of a mimicry complex. As described on BugGuide, “members of this complex present a confusing array of blue-and-black butterflies in the summer months in the eastern United States.” The arc of orange spots on the underside of the hindwind, clearly visible in the photo above, is a key to distinguishing this species from other members of the complex.

The other key was the host plant. Of course, Pipevine Swallowtail would lays its eggs on Pipevine, in this case, Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine. This plant was a rare find; I’ve never seen it offered again, or elsewhere. A few years ago, I visited Gowanus Nursery – my favored retail source for native plants in Brooklyn, even New York City – and asked if they had any Dutchman’s Pipe. I was hoping for A. macrophylla, a species with huge leaves, and a Victorian gardener’s favorite. They had some Aristolochia, but neither of us could id the species. Adventurous gardener that I am, I took a chance and brought home a quart specimen with a few, thin stems and small leaves. When it eventually bloomed, I was able to id it.

A few years later, the plant is huge, with dense foliage, though the leaves have remained small. It keeps reaching upward several feet, self-supporting its lax stems, and climbing into the cherry tree above it. It serves to screen the composting area from the rest of the garden. I think the mature growth of this plant, rather than the habitat plaque, is what attracted the butterflies to my garden, and select this plant as a host.

Eggs of Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail on Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine

Where I could find them, the eggs were laid only on the young leaves and petioles of fresh growth. This growth is abundant on the mature plant. The eggs are small, especially compared to the depth of the “hairs” of the plant. I suspect laying the eggs on young growth is critical to successful feeding by the young caterpillars. As they get larger, they can manage the larger, coarser hairs and leaves of more mature growth.

Empty eggs of Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, on Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine. Leaf removed from the vine and U.S. quarter coin provided for scale.

Just five days later, on June 2, the eggs hatched. Newborn caterpillars!

One day after they hatched, I found a group of four little caterpillars on the underside of a different, but nearby, leaf. Two days later, the group was down to three, and three days later, only two caterpillars were left on the leaf. The feeding damage visible in the photos is distinctive: other leaves on the vine have showed signs of feeding, or other uses, but nothing like the fine ragged edges left by tiny little mouths. I haven’t caught them in the act of feeding; I wonder if they feed at night, to avoid detection when active, and remain hidden during the day?

I’ve lost track of the caterpillars now. The vine is dense, with layers of foliage, and many twisting stems. I’ll watch for feeding damage to try to locate and photograph some of them again as they get larger. I’ll also look for chrysalises; catching them emerging as butterflies would be fantastic luck.

Aristolochia tomentosa is native to eastern and southern North America.

Battus philenor hosts on all species of the genus, so its range covers most of North America.

So, how is any of this “easy to replicate”? While flowers provide food to, and the plants shelter, adult butterflies and moths, a host plant meets three of the four habitat requirements: shelter, food, and a place to raise young. Most native plant species are known to host something. Both Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) and the international HOSTS Database from the Natural History Museum in London are online resources you can use to discover Lepidoptera-plant host associations.

A single container of a grass or sedge on a balcony can provide habitat. The whole of the cumulative impact of scores, hundreds of such micro-habitats will be greater than the sum. Even in urban settings, we can create opportunities for nature to return and thrive, and by reconnecting with it, we thrive as well.

[goo.gl]

Related Content

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, Flickr photo set

Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine, Flickr photo set

Links

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, BugGuide

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA)

Battus philenor host plants, HOSTS: World’s Lepidopteran Hostplants Database

Aristolochia tomentosa Sims, woolly dutchman’s pipe, USDA PLANTS Database (Synonym: Isotrema tomentosa (Sims) Huber)

Isotrema tomentosum (Sims) H. Huber, NY Flora Association Atlas (Does not list as present, let alone native, in NY)

Congrats on being certified as a wildlife habitat. That is so cool. I love the photos of the stages of the butterfly eggs to catepillar stage. Pretty neat!

What a great garden you have there. I am so happy for you; earning that nice habitat plaque. Keep up the good work. I know you're busy today with the visitors to your garden so have a great day. Love, Mom

Lovely post, great photos! By chance, would you want any birdfeeding stuff? I no longer have suitable habitat and it's just been sitting in a closet.

Fantastic photos of those tiny caterpillars! Pipevine & Pipevine swallowtails are fantastic.

Wonderful photos of the eggs and caterpillars. It's not often we get the opportunity to see these.

The Dutchman's Pipe flower is great too.

Very nice documentation of your pipevine swallowtail.

You should know that B. philenor is common in the deep south, but increasingly rare northward. Around New York City, it is highly local, clustered around the coastal areas of the boroughs, and up the Hudson along the Palisades, but infrequent to the north. Gardeners can encourage them by cultivating Aristolochia. If you plant it, they will come. It is believed that the former widespread planting of pipevines (Victorian times) helped spread the butterfly beyond it's primary range. Since it is in a lock-step with pipevines, it is one insect that can be encouraged without backlash consequences. As for the adults competing with others for flower nectar–well, plant more flowers!