[First in what I hope will be a series of Frequently Asked Questions, FAQs. If you have any questions for me, I invite you to leave a comment, or ping me on Twitter.]

Question: Where do you get your plants?

Answer (short)

I specialize in gardening with native plants. I get my plants from a variety of sources, including mail-order nurseries, local and regional nurseries, annual plant sales, and neighborhood plant exchanges. My Native Plants page has a list of Retail Sources of Native Plants in and around New York City, extending to New England and the Mid-Atlantic.

Grasses and Sedges at Rarefind Nursery in Jackson, New Jersey

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

Answer (longer)

I’ve been gardening in New York City for over three decades, since 1981 or thereabouts in the East Village, since 1992 in Brooklyn. Each garden provided its own challenges, and lessons. The plants I seek out, and where I get them, has changed a lot over time.

The first 20 years: Shade, Concrete, and Invasives

The first garden, in the East Village, was surrounded by adjacent buildings and overtopped by two large Ailanthus altissima trees (the “tree that grew in Brooklyn”). There I learned, by necessity, about gardening in shade. Garden #2, in Park Slope, was nearly all concrete; there I learned to garden in containers. Garden #3, also in Park Slope, had been somewhat neglected; weeds and invasive plants, including Fallopia japonica, Japanese Knotweed, were the lessons there.

I’ve always included native plants in my gardens. In the East Village garden, I planted a small wildflower area that was, perhaps, my favorite spot. I added a small wildflower plot to the 3rd garden, as well. Out of necessity, most of these were cultivars, the only “native plants” commercially available at the time. I divided many of them and brought them to my current garden.

The 4th Garden

This Spring will be 10 years since we closed on our current home, and I started work on my fourth garden in New York City. Here the lessons have been about rehabilitation, and healing the land, if only in my small pocket of it.

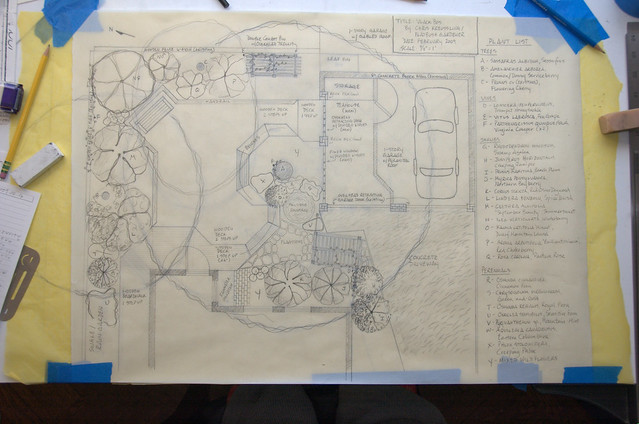

The backyard was the initial focus of my efforts. My goal here was to recreate a shady woodland garden, populated with native woodland plants. Four years in, it was my design subject for the Urban Garden Design class I took at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

10 years ago, the backyard was a wasteland of dust and scraggly grass, shaded by multiple Norway maples.

The first month, I removed four trees from this small space. Over time, the remaining three trees failed and had to be removed. After 10 years, I’m still working on building up the soil to meet the needs of more specialized woodland plants. But I’ve been largely successful in rehabilitating this space.

Similarly, the front yard was, at best, barren: lawn and a few canonical evergreen shrubs.

Our house was built in 1900. In keeping with the historical nature of our home, and the neighborhood, initially I focused on heirloom plants in the front garden.

As my knowledge of and experience with gardening with native plants grew, I expanded the scope of their planting to include all areas around the house. The loss of our neighbor’s street tree a few years ago to Hurricane Irene opened up – literally – the opportunity to grow more sun-loving species in the front yard. I started taking out the front lawn two years ago, gradually replacing it with a mixed wildflower meadow. The original lawn has been reduced to a less than a third of its original extent.

Most recently, I’ve narrowed my plant acquisitions further. My most treasured plants in my gardens are local ecotypes, those that have been propagated – responsibly – from local wild populations. There are two regional plant sales where these are available, both organized by regional preservation groups: the Long Island Native Plant Initiative, and the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. These are currently my preferred sources for plants.

It’s my hope that more retail sources for local ecotypes will become available to urban gardeners. I recommend that gardeners who want to explore gardening with native plants choose straight species, not cultivars, from local growers, who are more likely to be growing plants propagated originally from local stock.

Related Content

Tags: Nurseries, Sources, Native Plants

Flickr photo sets:

The Front Garden

The Backyard

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

Rarefind Nursery, Jackson, NJ

Links

Long Island Native Plant Initiative (LINPI) Plant Sale

Pinelands Preservation Alliance Plant Sale