Normally, this time of year would be busy with garden tours, workshops, talks and lectures, plant swaps and sales. In past years, my garden has been on tour for NYC Wildflower Week. Two years ago I spoke at the Native Plants in the Landscape Conference in Millersville, Pennsylvania. Last June I hosted the most recent of my Pollinator Safaris in my garden.

I had multiple engagements planned for this Spring, and into the Summer. I was going to speak on a panel about pollinators in NYC. This past weekend would have been the 10th Anniversary of the Great Flatbush Plant Swap, of which I was one of the founders. I would have been doing hands-on workshops on gardening with native plants in community gardens.

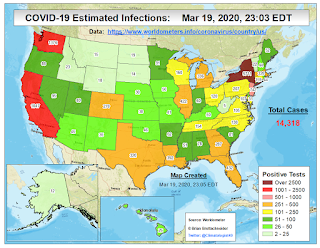

This year there is none of that. The reason, of course, is the global pandemic, COVID-19, caused by the coronavirus known as SARS-CoV2.

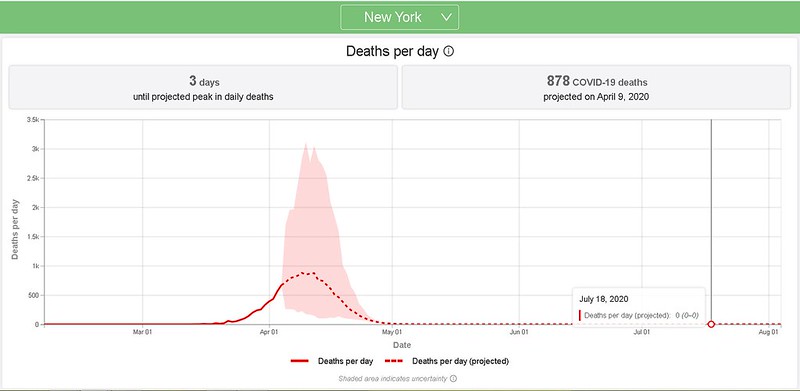

As I write this, I have been working from home for 8 weeks. The same week I started working from home, the first death from COVID-19 was recorded in New York City. Now, less than 2 months later, nearly 20,000 are dead.

We still have 200 dying every day. This is not anywhere near “over”.

The language and lessons of trauma – and recovery – are what we need to embrace right now.

Unavoidably, for me, have been the parallels with the AIDS epidemic. Unparalleled disparities in wealth built over decades, and systemic racism sustained over centuries, ensure that the epidemic does not affect all equally. A corrupt administration targets those it considers its enemies, cynically allowing who oppose it to die, a deliberate genocide.

In March of 1996, I had just started reading Walt Odets’ “In the Shadow of the Epidemic: Being HIV-Negative in the Age of AIDS”, the first book I read which gave voice to feelings shared by many of my cohort, gay men of a certain age: survivor guilt, and a spiritual crisis which has ravaged many of us. I wrote:

March 1996

so far surviving

what will it mean to be alive

having outlived generation after generation

decades of death

the explosion widening until, finally

and yes, with some grim, righteous satisfaction

finally noone can truthfully say

they are not also affected

imagine how it will be

when your closest friends are strangers

when long ago you gave up hope

of growing old together

as everyone you’ve loved, and despised

has died, seven times over

when you’ve learned, and loved, and lost

and learned, loved, lost

and …

When each new friend is met with the knowledge

that they too will leave soon

but it no longer matters

because, you think, you’ve already grieved their deaths too

the corpses pile up

against the walls you’ve built around yourself

walking along familiar streets

past the bars, your old haunts

you see tombstones, crosses, ashes

and you’re not safe, even in your own mind

especially at night

when the walls must come down

and you must remember the dead

you want to believe you’ve come so far

but it hasn’t even begun

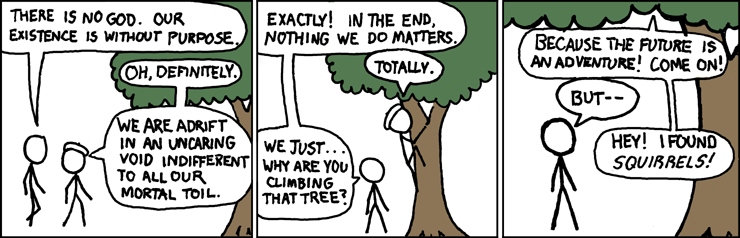

This is where we are – where we all are – now. Our bodies cannot physically sustain for months on end our initial response to the sudden changes we experienced with the epidemic. When we must survive, even against a low-level persistent threat, our brains rewire themselves. We are collectively immersed in what is aptly called endurance trauma.

But I feel no satisfaction from it.

I am grateful that both my husband and I are able to work from home. We continue to adapt, in both large and subtle ways, to being forced to be around each other nearly constantly.

For my part, I take advantage of every good weekend day, and long daylight hours, to garden as much and as long as I can. I have been removing non-native plants – mostly the Iris and daylilies – to make room for planting more native plants. And, for the first time in years, to grow some food crops.

Since there would be no Great Flatbush Plant Swap this year, I decided to give away the plants as I removed them. I have been giving away plants from my own garden for weeks, now. While my initial intent was to solve a problem I had in my garden, it’s turned into much more.

I’m having conversations with neighbors and passersby, checking in with each other about how we are handling the situation. These visits often turn into mini garden tours and educational talks about how to garden for habitat, inviting even more life to co-reside with us, healing the urban ecology as we nourish our own connections to the natural world.

Whatever green people can grow sustains them psychologically. These new “victory gardens” are a form of defiant gardening, which Kenneth Helphand so beautifully wrote about in his book of the same title. It is a way of coping with, and defying, endurance trauma.

The following comes from an open latter I wrote on October 15, 2001, barely a month after the September 11 attacks, to Joanna Tipple, then pastor of the Craryville and Copake Churches in New York State.

As I tend my garden, I recall how it was a minute, a day, a year ago. That flower was, or was not, blooming yesterday. This plant has grown over the years and now crowds its neighbors. A label in the ground shows where another plant has vanished. Should I replace it, or try something new? I weed. I plant. I water. I sit. The garden asks me to see it as it really is, not just how I remember it, or how I wish it to be. Gardening continues to teach me many lessons. Gardening is my prayer.

So I must be in the world. Remembering what was. Observing what is. Hoping for what can be. Acting to bring it into being. When we struggle to understand, we question what is. Science can ask, and eventually answer, “What?” and “How?” It cannot answer the one question that matters, the question for which Man created God: “Why?” Now, as with each new loss, I ask again: Why am I here? Why am I alive?

The only answer I’ve come across which satisfies me at all comes from Zen: The purpose of life is to relieve suffering. Not to relieve pain, or grief, or loss. These cannot be avoided. But to relieve suffering, which we ourselves bring into the world. Because death is senseless, the only sense to be found is that which we manifest in our own lives. The only meaning there can be in life is what we impart.

Victor Frankl, a survivor of the Nazi holocaust, wrote “What is to give light must endure burning.” Light doesn’t justify burning. Light transcends burning.

We are enduring, now. Whether we know it or not. Whether we acknowledge what we feel, or not. We must also do more than endure. How we celebrate ourselves transcends what we must endure and survive. It serves only our enemies – and serves us least of all – to be polite, nice, and “normal,” to be unassuming and inoffensive, to be silent and invisible.

Illustration by Enkhbayar Munkh-Erdene for YES! Magazine, from a self-portrait I took of myself in my backyard.

Related Content

NYC in the time of COVID-19

.jpg)