Tag Archives: Ecology

Charismatic Mesofauna

Over the weekend I was inspired to write a little tweet storm. I thought it would make a good blog post.

It started with a blog post by entomologist Eric Eaton, who goes by @BugEric on his blog, Twitter and other social media. Benjamin Vogt, a native plants evangelist (my word, bestowed with respect) tweeted a link, which is how it came to my attention.

The Monarch is the Giant Panda of invertebrates. It has a lobby built of organizations that stand to lose money unless they can manufacture repeated crises. Well-intentioned as they are, they are siphoning funding away from efforts to conserve other invertebrate species that are at far greater risk. The Monarch is not going extinct.

– Bug Eric: Stop Saying the Monarch is a “Gateway Species” for an Appreciation of Other Insects

I grow milkweed in my garden – at least 3 different species. (I’m waiting to see if the other 3 species persist and return.) I’ve documented monarch butterflies visiting the past 2 years. Last year I got eggs, and caterpillars.

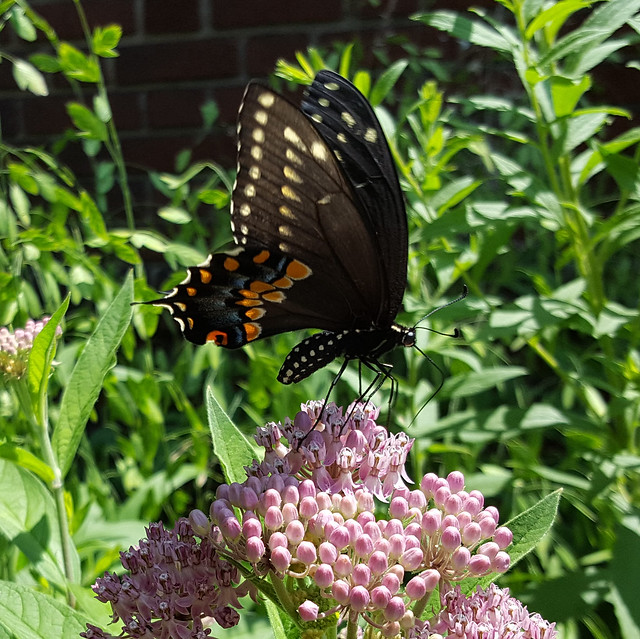

But monarchs aren’t the only visitors to my milkweeds.

A popular argument for making the Monarch an invertebrate icon is that “being such an icon has really helped us reach the average person about habitat and native plants and conservation, and by extension, the environment and climate change,” as one friend on social media put it. Well, if only that were true. If people who care about the Monarch had any understanding of ecology at all, they would not be complaining that “there are beetles eating the milkweed I planted for Monarchs!” They would not be devastated because one wasp killed one of the caterpillars.

As Eric noted in his article, gardeners who fret over “what’s eating my milkweed” are valuing their monarchs over the other invertebrates. Like these aphids.

Like the monarchs, their bright orange color is aposematic, warning potential predators of their milkweed-borrowed toxicity. No matter … They sustain other visitors, like this brown lacewing larva.

Or this Ocyptamus fuscipennis, syrphid/flower fly, showing great interest in the aphids on Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed, in my front yard.

And who knows what this Hymenoptera was hunting for.

And there are other floral visitors besides the charismatic butterflies.

There are many more I’ve yet to identify. All this on just three species of plants in my garden. Plants that some would grow only for the monarchs.

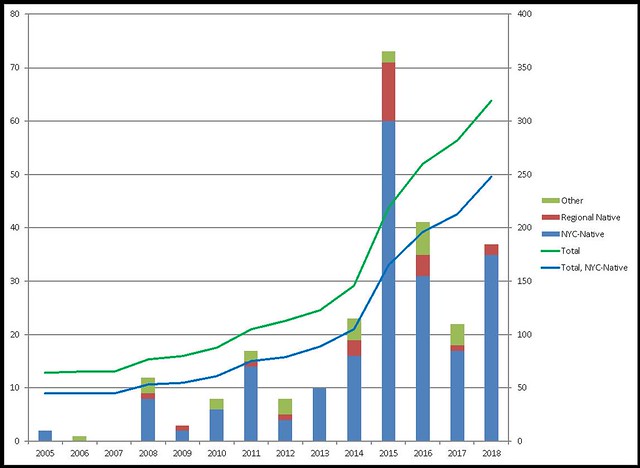

I’m growing over 200 species of plants native to New York City, and another 80 or so regional natives.

With all that botanical diversity has come insect diversity:

- 31 species of bees.

- 28 species of wasps.

- 23 species of flies.

- 20 species of beetles.

And, oh yeah, 24 species of butterflies, moths, and skippers. Including the charismatic monarchs.

| Family | Common Name | # Species |

| Coleoptera | Beetles | 20 |

| Diptera | Flies | 23 |

| Hemiptera | Bugs | 9 |

| Hymenoptera | Bees | 31 |

| Hymenoptera | Wasps | 28 |

| Lepidoptera | Butterflies, Moths, and Skippers | 24 |

Let’s plant milkweed, just not only for the monarchs.

And not just milkweeds.

Oh, and no pesticides.

Thank you.

Related Content

Blog Posts

Flickr photo sets

Danaus plexippus, monarch butterfly

Milkweed species I’m growing in my garden. (Not all the photos are taken from my garden.)

Links

Bug Eric: Stop Saying the Monarch is a “Gateway Species” for an Appreciation of Other Insects

A milkweed by an other name …

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

– Juliet, Romeo and Juliet, Wiliam Shakespeare

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.

– Gertrude Stein, various

I started to get into a little tiffle on a post (since removed) on one of the insect ID groups in Facebook. The original poster was trying to ID a tight cluster of orange eggs on a leaf of a plant she identified as “milkweed vine.” One of the responders commented: “Milkweed vine? Not likely.” And then we were off.

What’s a “milkweed,” anyway?

Responding in a comment, the original poster specified that the plant was Morrenia odorata, an introduced, and invasive, vine in the Apocynaceae, the dogbane family. (Some authorities still list it under Asclepiadaceae, the milkweed family, which is now considered a sub-family, Asclepiadoideae, of Apocynaceae.) Its common names include latex plant, strangler vine, and, yes, milkweed vine.

The responder’s objection was that “Aclepias is milkweed.” Period. Final. Absolute declaration.

It’s not that simple.

Common names like “milkweed” have no authority. Many plants have “milkweed” as part of their common name, not just Asclepias species. Cynanchum laeve, a native vine in the same family as Morrenia and Asclepias, has a common name of climbing milkweed, among several others.

Noone can claim that only Asclepias species can be called “milkweed.” To insist so is, at best, dismissive. I would use stronger language. (I blocked the responder on Facebook to avoid future tiffles with them.)

Why plant ID matters for insect ID

Why did the original poster include the id of the plant in their requesting for identifying insect eggs? Because they understand that many insect species depend on different types of plants. Specialist insect-host associations are common in the co-evolutionary biochemical arms race between insect herbivores and their host plants.

Only five years ago, I didn’t have any knowledge of insect-host plant relationships. Marielle Anzelone (@NYCBotanist on Twitter – follow her!) clued me in on what was going on when I observed this in my backyard in May 2011:

I recognized it as a swallowtail. Knowledge of the plant – Aristolochia tomentosa, wooly dutchman’s pipevine – id’d the butterfly as pipevine swallowtail, Papilo troilus. The caterpillars of this species feed only on plants in the Aristolochiaceae, the pipevine family, primarily – but not exclusively – Aristolochia species.

And so it is with “milkweeds” and their most famous herbivore, the caterpillars of monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus.

The butterflies nectar on a wide variety of flowers. Their caterpillars, however, are specialized feeders on plants in the Apocynaceae. While they are most commonly associated with Asclepias species, they have also been observed on Cynanchum and Apocynum species. They have even been observed on a few plants outside of this family.

So, when trying to identify insects, knowledge of plants, plant families, and their ecological associations is also important. Being pedantic about common names, not so much.

Related Content

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, Flickr photo set

Danaus plexippus, monarch butterfly, Flickr photo set

Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine, Flickr photo set

Danaus plexippus, monarch butterfly, Flickr photo set

Aristolochia tomentosa, Wooly Dutchman’s Pipevine, Flickr photo set

Links

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, BugGuide

Battus philenor, Pipevine Swallowtail, Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA)

Battus philenor host plants, HOSTS: World’s Lepidopteran Hostplants Database

Danaus plexippus host plants, HOSTS: World’s Lepidopteran Hostplants Database

Aristolochia tomentosa Sims, woolly dutchman’s pipe, USDA PLANTS Database (Synonym: Isotrema tomentosa (Sims) Huber)

Isotrema tomentosum (Sims) H. Huber, NY Flora Association Atlas (Does not list as present, let alone native, in NY)

Danaus plexippus host plants, HOSTS: World’s Lepidopteran Hostplants Database

Garden Deeper

I had a visceral (in a good way) reaction to Adrian Higgins’ writeup of a visit, with Claudia West, to Shenk’s Ferry Wildflower Preserve.

I think I’ll adopt “ecological horticulturist” to describe my own approach to gardening. Whether you specialize in gardening with native plants, as I do, or prefer to grow plants from around the world, studying their native habitats is, in my experience, the best way to learn how to grow them in a garden.

That doesn’t mean you have to recreate the conditions exactly. In many cases, this is impossible, anyway. The native Aquilegia canadensis, eastern red columbine, thrives in the crumbling mortar of my front steps; this location recreates some aspects of the face of a limestone cliff where I saw, decades ago, a huge colony of them in full bloom.

This is why I’m trying to go on more botanical walks and hikes. Like many, if not most, gardeners, I’ve never seen most of the plants I grow in the wild. I visited Hempstead Plains for the first time in August 2013.

That inspired me last year to remove most of the remaining lawn in the front yard and approach it as a meadow, instead.

Rain gardens and rock gardens are both examples of creating gardens to grow plants requiring specific conditions, and to meet human needs. But we don’t need to go to so much trouble. For all the “problem areas” in our gardens, there are plants that want nearly exactly those conditions. We need only think like a plant to see these as opportunities, and embrace the habitats waiting to emerge.

Related Content

Links

What you can learn from a walk through the woods (with Claudia West), Adrian Higgins, Washington Post Home & Garden

Pine Barrens Soil Horizons

Yesterday, I transplanted a small piece of Carex pensylvanica, Pennsylvania sedge, from my sister’s property in Ocean County, New Jersey. This species is common on her property.

She lives in the pinelands of New Jersey. The canopy is pine and oak. The duff layer – the natural “mulch” of dead plant material deposited on top of the soil – is composed of mostly pine needles, with some oak leaves.

Here’s a view of the clump I extracted.

And here’s the “back” view, where the blade of the spade I was using sliced through.

I only just realized I had a nice slice of the upper soil horizons.

The slats of the tabletop are 2″ wide. The entire depth of the soil slice is only about 3″, 4″ including the duff layer.

The white is fungal mycelium that has colonized the duff layer, starting the process of decomposition.

After I moved this clump from the table, I noticed tiny beetles, at least two different species, had clambered off. They fell through the slats before I could photograph them or otherwise observe them more closely for identification.

This small slice represents at least five different macro-species – pine, oak, sedge, and beetles – and one micro: the fungus. If we could somehow inventory all the micro-invertebrates and micro-organisms, there might be hundreds, or thousands, of species in this photo.

It’s tempting to think of species as singular “things,” to be contained in our cabinets of curiosities, our checklists, our collections. Any species is not any one thing, but a population, containing genetic diversity that slowly shifts and drifts across space and time. Each species is part of a larger whole, an unbounded fractal of complex relationships.

Yes, I grow many native plant species in my garden. For one reason, I can learn to recognize them. I never want to forget how artificial my construction is. However I may hone my garden, whatever beauty I can construct here, and pleasure I may offer from it, it doesn’t compare to the transcendence I experience of wild things in their natural habitats. All this diversity at home reminds me of how much more there is, still, in the world, and how important it is to protect it.

Related Content

Links

Pollinator Gardens, for Schools and Others

I got a query from a reader:

I’m working on a school garden project and we’d like to develop a pollinator garden in several raised beds. Can you recommend some native plants that we should have in our garden? Ideally we’d like to have some perennials and maybe a few anchor bushes. Are there any flowers that we might be able to start inside this spring then transplant? Also, because the students will be observing the pollinators, butterfly attracting plants are preferable to the teachers.

Whole books have been written on this topic, but here are some quick thoughts and references for further research.

Design Notes

- How much space is available for the garden? That will determine how many shrubs could be accommodated. Layout the woody plants first, then plan blocks of plants through the rest of the beds.

- Is it sunny? Shady? Mixed? Trees nearby? That will determine the types of plants that can be grown. Pollinators are more active in the sun, but you can still get plenty of action in shadier gardens. Just make the most of the sun and light you get throughout the day.

- How will it be watered while getting established? Who will water it? What happens during the summer while school is out? After the first year, once established with the right plant selections, watering needs should be minimal.

- Are the raised beds already established, or will they be filled with soil? Many “pollinator” plants fare languish in the rich soils prepared for the vegetables and edibles more typically grown in school gardens, and would prefer ordinary, even “poor,” soils.

- Plant multiples of the same plants in groups and patches, to make them easier for pollinators to find. It also provides a more continuous supply of nectar: if one flower or plant runs dry, another in the same patch can provide.

- See more about what to plant, below.

Plan for Pollinators

Pollinators visit flowers for two main reasons: nectar and pollen. We want to create habitat, not just a buffet. Plan to address the four basic needs: water, food, shelter, and a place to raise young. Host plants are just as important as flowers.

2-day old caterpillars of Battus philenor, pipevine wallowtail, on Aristolochia tomentosa, wooly dutchman’s pipevine, in my garden, June 2011

Even if we limit consideration to insect pollinators, there are many different kinds, including bees, wasps, flies, beetles, butterflies, and moths. Everyone wants butterflies, the divas of the garden. Some are squeamish about bees and wasps, but they really don’t bother people. Any flowers you grow will attract them, so they’re part of the garden already.

Multiple Pollinators on Pycnanthemum muticum, Clustered Mountain-Mint, in my garden, August 2011

Bees, of course, are all-around the most effective pollinators. But not just honeybees. There are scores of native bee species happy to take up residence in a garden.

Multiple nest entrances of Colletes thoracicus (Colletidae), Cellophane Bees, in my garden, May 2008

You can setup nesting boxes for native mason bees and carpenter bees. They’re fascinating to watch, and you can see how the nest tubes get occupied over time.

Bee Houses at the Greenbelt Native Plant Center, Staten Island, May 2010

Monarch butterflies are in steep decline and need our help. Milkweeds are their preferred host plants, so planting milkweeds is the best thing you can do to help monarchs. Several milkweed species are native to NYC. Many other pollinators are attracted to the flowers, as well.

NYC-local ecotype of Asclepias incarnata, Swamp Milkweed, in my garden, June 2008

Plant Native

- To get the greatest number and diversity of pollinators, choose plants that have clusters of many small flowers, such as plants in the Asteraceae (asters, daisies, sunflowers, goldenrods, etc) and Lamiaceae (mints) families.

- Include plants that bloom at different times of the year – especially very early and later in the year, when flowers are scarce – to provide a continuous supply of food for both adults and their young.

- Differences in flower size and structure affect which pollinators they can support.

- Insect-host plant associations can be very specific. Plants from different families support different species. So diversify the plant families you grow.

- Plant as many different species as your space can accommodate.

- Don’t forget to use the vertical space: include plants that grow taller and shorter.

- Plant in masses and blocks. Pollinators recognize they’re more likely to find pollen and nectar when several different plants, with many different flowers blooming at different stages, are available to choose from.

- The best plants for pollinators are native to the region, and – as much as possible – from local stock. This is true for both nectar and host plants. Prefer native species over non-native, straight species over cultivars, propagated from local populations over more distant ones.

I adapted this chart from published results of the Pollinator Plant Trial (PDF, 3 pp) at Penn State Southeast Agricultural Research and Extension Center (SEAREC)

My authority for “What’s native?” in my region is the NY Flora Atlas. You sometimes have to watch out for changes in nomenclature, but it’s an excellent resource. Resources for our adjacent states are the Native Plant Society of New Jersey and the Connecticut Botanical Society.

Your best bet for obtaining plants propagated from local stock is to work with nurseries based near you that specialize in native plants. In my area, for starting native plants from seed I recommend Toadshade Wildflower Farm located nearby in New Jersey. They have an astonishing range of native plants available, and seed for many of them. They’re passionate, experienced, and know their plants.

Related Content

FAQ: Where do you get your plants?

The 2014 NYCWW Pollinator Safari of my Gardens

Gardening with the Hymenoptera (and yet not), 2011-07-31

Gardening with the Lepidoptera, 2011-06-11

My blog posts on Butterflies (Lepidoptera), Bees and Wasps (Hymenoptera), Pollinators, Habitat, and Ecology

My Native Plants page

Retail sources for native plants

Me hosting the NYCWW Pollinator Week Safari in my Front Yard, June 2014. Photo: Alan Riback

Links

NY Flora Atlas

Native Plant Society of New Jersey: Plant Lists

Connecticut Botanical Society: Gardening with Native Plants

Biota of North America Program (BONAP): North America Plant Atlas (NAPA)

USDA PLANTS Database

Pollinator Partnership: Regional Planting Guide

Center for Biological Diversity: Native Pollinators

Xerces Society: Bring Bank the Pollinators

Wikipedia: Pollination Syndrome

Toadshade Wildflower Farm

NYC Wildflower Week

Research

Specialist Bees of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States

Megachile, Leaf-Cutter Bees

A leaf-cutter bee removes a segment from a leaf of Rhododendron viscosum, swamp azalea, in my urban backyard native plant garden and wildlife habitat (National Wildlife Federation Certified Wildlife Habitat #141,173). You can see other segments – both completed and interrupted – on the same and adjacent leaves.

Like carpenter bees, Leaf-cutters are solitary bees that outfit their nests in tunnels in wood. Unlike carpenter bees, they’re unable to chew out their own tunnels, and so rely on existing ones. This year, I’ve observed a large leaf-cutter – yet to be identified – reusing a tunnel bored in previous years by the large Eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica.

They use the leaf segments to line the tunnels. The leaves of every native woody plant in my garden has many of these arcs cut from the leaves. The sizes of the arcs range widely, from dine-sized down to pencil-points, reflecting the different sizes of the bee species responsible.

Tiny arcs cut from the leaves of Wisteria frutescens in my backyard.

I speculate that different species of bees associate with different species of plants in my gardens. The thickness and texture of the leaves, their moisture content, and their chemical composition must all play a part. I’ve yet to locate any research on this; research, that is, that’s not locked up behind a paywall by the scam that passes for most of scientific publishing.

Although I’ve observed the “damage” on leaves in my garden for years, this was the first time I witnessed the behavior. Even standing in the full sun, I got chills all over my body. I recognize now that the “bees with big green butts” I’ve seen flying around, but unable to observe closely, let alone capture in a photograph, have been leaf-cutter bees.

As a group, they’re most easily identified by another difference: they carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen. A bee that has pollen, or fuzzy hairs, there will be a leaf-cutter bee.

An unidentified Megachile, leaf-cutter bee, I found in my garden.

Another behavior I observe among the leaf-cutters in my garden is that they tend to hold their abdomens above the line of their body, rather than below, as with other bees. Perhaps this is a behavioral adaptation to protect the pollen they collect. In any case, when I see a “bee with a perky butt,” I know it’s a leaf-cutter bee.

When they’re not collecting leaves, they’re collecting pollen. Having patches of different plant species that bloom at different times of the year is crucial to providing a continuous supply of food for both the adults and their young.

An individual bee will visit different plant species (yes, I follow them to see what they’re doing). And different leaf-cutter species prefer different flowers. All the plants I’ve observed them visit share a common trait: they have tight clusters of flowers holding many small flowers; large, showy flowers hold no interest for the leaf-cutter bees.

Related Content

Links

A Hudson River Riparian Plant Community

Part of the eastern bank of the Hudson River, just south of the Route 8 bridge at Riparius/Riverside in the Adirondacks of New York. A year ago, this was all underwater, inundated by flood waters from Hurricane Irene.

One year ago, Hurricane Irene reached New York City. The damage in my neighborhood was slight: downed trees and large tree limbs.

Our post-engagement pre-honeymoon vacation was delayed a day, simply because there were no roads open out of the city to our destination. Even the New York State Thruway was closed along most of its length: many entrance and exit ramps flooded, and it was safer to keep people off the road altogether.

Irene’s rains continued north, devastating the Catskills. At New Paltz, the Wallkill River overtopped its banks. This was a cornfield; the entire crop was lost. The sunflowers at the far end of the field are ten feet tall.

The rains reached the Adirondacks. Which was exactly where our vacation plans were taking us. We arrived at Riparius, NY, on the banks of the Hudson River in the Adirondacks, just after Labor Day 2011, a few days after Irene had passed and the rains subsided.

The river was still swollen a few feet above its normal level. Never having been there before, I had no frame of reference. But I could see the waters lapping onto the lawns below the cabins, and saw grasses flowing beneath the waters. The few rocks visible were submerged, or nearly so.

Last week we arrived at a different river, the wild Hudson, still freshly scrubbed and scoured by Irene’s floodwaters. The water, and banks, are now dominated by smooth, polished river rocks. In Adirondack tradition, I constructed a cairn on the shore near the cabin where we were staying.

The evidence of Irene was everywhere. In addition to the plentiful now-exposed rocks, bank erosion was visible nearly the entire length of the shoreline here, cutting back into the mowed lawns hosting Adirondack chairs sited to view the sunset over the Hudson. The rocks themselves seemed relatively little disturbed. What Irene did was clear away a good foot or so of soil and plant growth that had overlaid the rocks, revealing the older, rocky bank beneath.

One can see here that larger rocks amplified the power of the moving waters around them, scouring away the soil that previously surrounded them. The absence of lichens on the upper surface of this rock indicates it probably was previously covered with at least a thin layer of soil and plant roots. Now, a year after Irene, it stands alone.

Remarkable, to me, was how much plant life remained among the rocks. Most of what’s visible in this photo was inundated a year ago. The line of erosion can be clearly seen along the right. In some places, a foot or more of soil was washed away with Irene’s floods. This exposed the rocky bank beneath.

A year ago, the water rose up onto the lawn on the upper right of the photo above. In this photo, just in front of the white bench, the rocky bank of the photo above is barely noticeable.

The grasses flowed underwater with the current, like seaweed.

But not all plants were washed away. Several clumps remained intact. Instead of wiping the slate clean, as Irene did in many places in the Catskills, the old set was struck and the stage reset for the next scene. The regeneration of a soft, soiled bank has already begun, as survivors recover, and pioneers fill in the now empty muck between the rocks.

Key to the persistence and recovery are the grasses, the dominant plants in this community. Here’s a detail demonstrating the tenacity of the roots, and their ability to grip bare rock and hold the soil in place against the floodwaters. And not just those of the grasses: one can also see here at least a half-dozen non-grass species growing in and around the grasses. They benefit from this close association simply by being present after the flood, ready to quickly regenerate and re-populate the landscape.

And thus begins the cycle. These plants – and some pioneer grasses – have already begun to restore themselves and their community. Over time, between floods, they will fill in all the gaps among the rocks again, laying down more organic material, and rebuilding the old, soft, green shore. Until the next flood.

The diversity of this plant community – just one year after the flood – surprised me. More evidence that most of these plants survived the flood, rather than colonizing the river just this year. I’m still identifying plants from the photos I took on this strip. And it will probably take me months to upload them all. But here’s a list of the species and genera I’ve been able to identify so far:

- Chelone glabra, White Turtlehead

- Cyperus strigosus, Umbrella Sedge

- Eupatorium/Eupatoriadelphus, Joe Pye Weed

- Helenium autumnale, Sneezeweed

- Iris, probably Yellow Flag

- Lobelia cardinalis, Cardinal Flower (easily identified as the spots of bright red in these photos)

- Lobelia kalmii, Kalm’s or Ontario Lobelia (also new to me, needed to get online before I could identify it with any confidence)

- Lycopus amaricanus, American Water-Horehound (a species new to me, I recognized it as a member of the Lamiaceae, mint family, which aided identification)

- Lythrum salicaria, Purple Loosestrife (Unfortunate, but I only found three scattered plants. Now would be the best time to remove them, but as a guest, and a stranger, it was not my place to do so on my own.)

- Mimulus ringens, Allegheny Monkey-flowe

- Myosotis, Forget-Me-Not (haven’t keyed it out yet to determine if it’s a native or introduced species)

- Polygonum amphibium, Water Smartweed (also new to me)

- Sanguisorba canadensis, American Burnet (another new species for me)

- Solidago, Goldenrod

- Spiranthes cernua, Nodding Lady’s-Tresses (also new to me, but I recognized the tiny flowers as orchids, which narrows it down considerably)

- Verbena hastata, Common Verbena (yet another new species for me)

The Adirondacks as we know them today are only 20,000 years old, exposed after the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (which also gave birth to Long island, including Brooklyn). My stone cairn may be a little sturdier than a sand castle, but its ephemeral nature is part of its charm, and its beauty. I see the river, the rocks, the plants, the mountains themselves with the same eyes. Because I will never see them this way again, they are all the more beautiful to me now.

[goo.gl]

Related Content

Flickr photo sets:

Plants:

- Chelone glabra, White Turtlehead

- Cyperus strigosus, Umbrella Sedge

- Helenium autumnale, Common Sneezeweed

- Lobelia cardinalis, Cardinal Flower

- Lobelia kalmii, Kalm’s or Ontario Lobelia

- Lycopus americanus, American Water-Horehound

- Lythrum salicaria, Purple Loosestrife

- Mimulus ringens, Allegheny Monkeyflower

- Polygonum amphibium, Water Smartweed

- Sanguisorba canadensis, Canadian Burnet

- Spiranthes cernua, Nodding Lady’s-Tresses

- Verbena hastata, Swamp Monkeyflower, Common Monkeyflower