There are three sections to this post:

Trinity

This is a flower border at one of my favorite gardens to visit. Earlier in the year, there has been a succession of Iris, Hemerocallis (Daylilies), Hosta, and other common and sturdy garden perennials. There are ferns, and flowering cherry trees on the grounds.

The garden is the cemetery at Trinity Church in downtown Manhattan, just down the block from Ground Zero. The photo above is looking south, toward the church itself. Here’s another view looking east, toward Broadway, which is just on the other side of the wrought iron fence surrounding the cemetery.

This really is one of my favorite gardens to visit. First off, I love cemeteries. During my troubled adolescence, a cemetery at the end of our street was a refuge for me, a place I could go where no one would bother me, a place of solitude, and quiet. I came to enjoy the history of it, reading the stones to learn about people’s lives, how young they died, how many of them were children, and infants.

This garden cemetery also reminds me of impermanence. When I walk through it, I’m on my way to work, in the financial district of downtown Manhattan. It’s easy to get stressed about work. This walk helps me keep a healthier perspective on things. Check out the engraving on this headstone.

“Here Lyes ye Body of John Craig Who Departed ths Transetorey Life September ye 14 1747 Aged 47 years” At 47 years, he was an old man when he died. He could have easily been a grandfather. And yet, “ths Transetorey Life” … Next week is the 259th anniversary of his death. How many lifetimes, how many generations, is 259 years?

Another thing I enjoy about visiting this garden cemetery is the ritual I’ve developed for entering it. There’s really only one way: from the Rector Street station on the R/W subway line. This lets me out on Church Street. After emerging from the subway, the streetscape is the photo below.

This is Church Street, looking north. Ground Zero (of which more below) is just one block away, where the buildings end on the left-hand side. On the right-hand side is a massive, and seemingly ancient, sandstone block wall. See the trees peeking out over the top of it? Those are from the garden cemetery. Here’s a view of the church from this vantage.

That’s right: the cemetery is two stories above your head. Behind those stone blocks are the dead. To reach the cemetery, we have to climb still further, through the street-level opening in the wall, of which we only see the top of its gothic arch in the photo above, and up another two flights of stairs. Lest one forget, the sculpture set in the stone above the passageway is no cherub.

Ground Zero

I wrote earlier this week about the arbitrariness of anniversaries. But I have been feeling this one, the 5th anniversary of 9/11. The city is feeling it, too. Peoples’ grief is closer to the surface, more accessible. Mine certainly is. I’ve also been remembering a lot of what it was like in the city right after. There are reminders of it everywhere, on the news, in the papers, special exhibits and events, and especially, at Ground Zero.

A Tribute Center was dedicated this week on Liberty Street, on the south side of Ground Zero. I’d heard about it and I went there after work on Thursday. The doors had signs on them which said “Closed.” There was a couple next to me also looking at the signs. Someone inside saw them and opened the door for them. I thought they were just closing for the day, and let us in anyway. I tailgated in. I didn’t realize that it’s not open to the public until September 18.

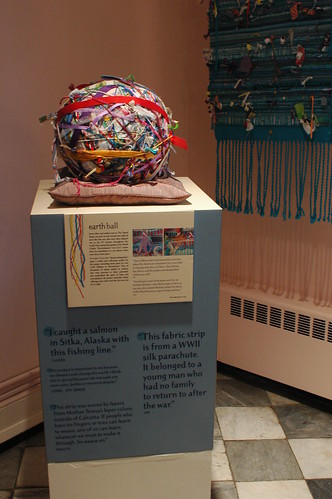

Anyway, it’s quite a collection. They have artifacts. It took me a while to figure out what this object was. When I did, it just shocked me. I didn’t have my camera with me, just my camera-phone/phonecam. It’s a lousy picture, and I’ll go back and get a better one.

Another thing which shook me was some photographs in one of the display cases. There was a contact print of a couple of frames from a still camera, with some clear problems with light leakage along the top of the frame. The text explained that these photographs were taken by a photographer on the scene. His camera was damaged, and he was killed, when the first tower fell. His camera and film were recovered, and those prints were made.

Outside the PATH (Light rail/Subway to New Jersey) station, on the fence surrounding the site, is an exhibit of photographs from September 11 and the recovery efforts. The photographs are incredible, from all different photographers.

The names of the photographers and explanations of each scene are displayed alongside the photos. I didn’t make notes of their names. I’m hoping I can find a catalog of them online somewhere. Here’s one of the photographs.

St. Paul’s

This shows the tower of St. Paul’s Church about to be engulfed by the debris cloud from the collapse of the first tower. I’m pretty sure this was taken from an office building to the east, looking west toward the church and the World Trade Center site. St. Paul’s is directly across the street from the PATH station, and just a couple of blocks up the street from Trinity Church.

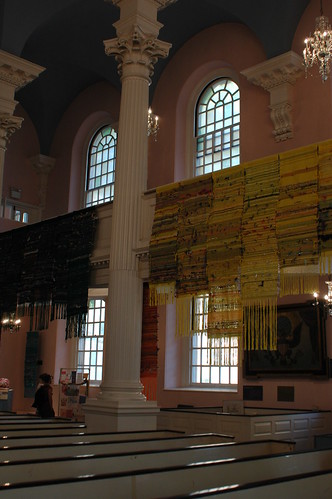

St. Paul’s sustained heavy damage, but it survived, and it served as one of the centers for recovery efforts downtown. Its fence was covered with memorials for months. Right now it’s housing the Threads Project, which collected threads, ribbons, and so on from all over the world and distributed it to weavers all over the world to create the works you see below.

One of the losses at St. Paul’s was a large Sycamore from the cemetery. If the tree had not been there, the church would have sustained even greater damage from debris which felled the tree instead. The tree has been captured as a symbol of the day, by casting its root system as a sculpture in bronze. This sculpture is permanently placed in a courtyard outside Trinity Church. The sculpture is called “Trinity Root.”

And so we’ve come full circle. From Trinity, to Ground Zero, to St. Paul’s, and back again. We grieve the loss of a great tree, whose death saved others’ lives, and celebrate it. We grieve the garden, and grieve through the garden. It’s the weekend before five years after. I will be mowing the lawn, weeding, maybe sifting some compost, and preparing the garden to receive the bulbs which should arrive in a few weeks. I will do all these ordinary things. And when I return to work on Monday, I will look up, and turn my face to the hole in the sky, and remember again.