Fall Colors around Lake Superior, September 23, 2007. Credit: NASA Terra–MODIS (Satellite-Sensor)

The autumnal equinox of 2007 occurred at 09:51 UTC on Sunday, September 23, or 05:51 Eastern Time. “Autumnal” instead of “Fall” because:

- It’s okay to use for both hemispheres.

- Also, you could use this term on any other planets on which you should find yourself.

In northeastern North America, we measure fall by the changes in foliage. And it’s on its way south from Canada.

The calendar may have set September 23 as the first day of autumn in 2007, but the forests that line the eastern shore of Lake Superior had already started to mark the turning of the season. By September 23, when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this photo-like image, the forests of northern Michigan and southern Ontario flamed orange as the first trees of the season—maples—began to display their brilliant red and orange fall colors. Veins of green run through the sea of orange where the deciduous forest gives way to deep green pine trees.

The most vivid color is concentrated in Canada’s Ontario Province. Located farther south, Michigan’s trees show only a hint of color. …

The large image provides an unusually cloud-free view of all of the Great Lakes. Similar spots of color stretch across southern Canada and parts of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The northern plains of the United States have started to turn yellow as grasses ripen, but the eastern forests in Pennsylvania and New York remain deep green.

New York State operates its own fall foliage watch. You can track the progress of the changes on the map provided on their Web site. They were predicting “vibrant, near-peak autumn color” this past weekend for the Adirondacks, the peachy area in northern New York state on the map below.

Here in NYC, we’re still in the green, but I’ve been watching the subtle changes. Individual trees in my neighborhood, including the cherry tree in my backyard, are already picking up shades of yellow and orange.

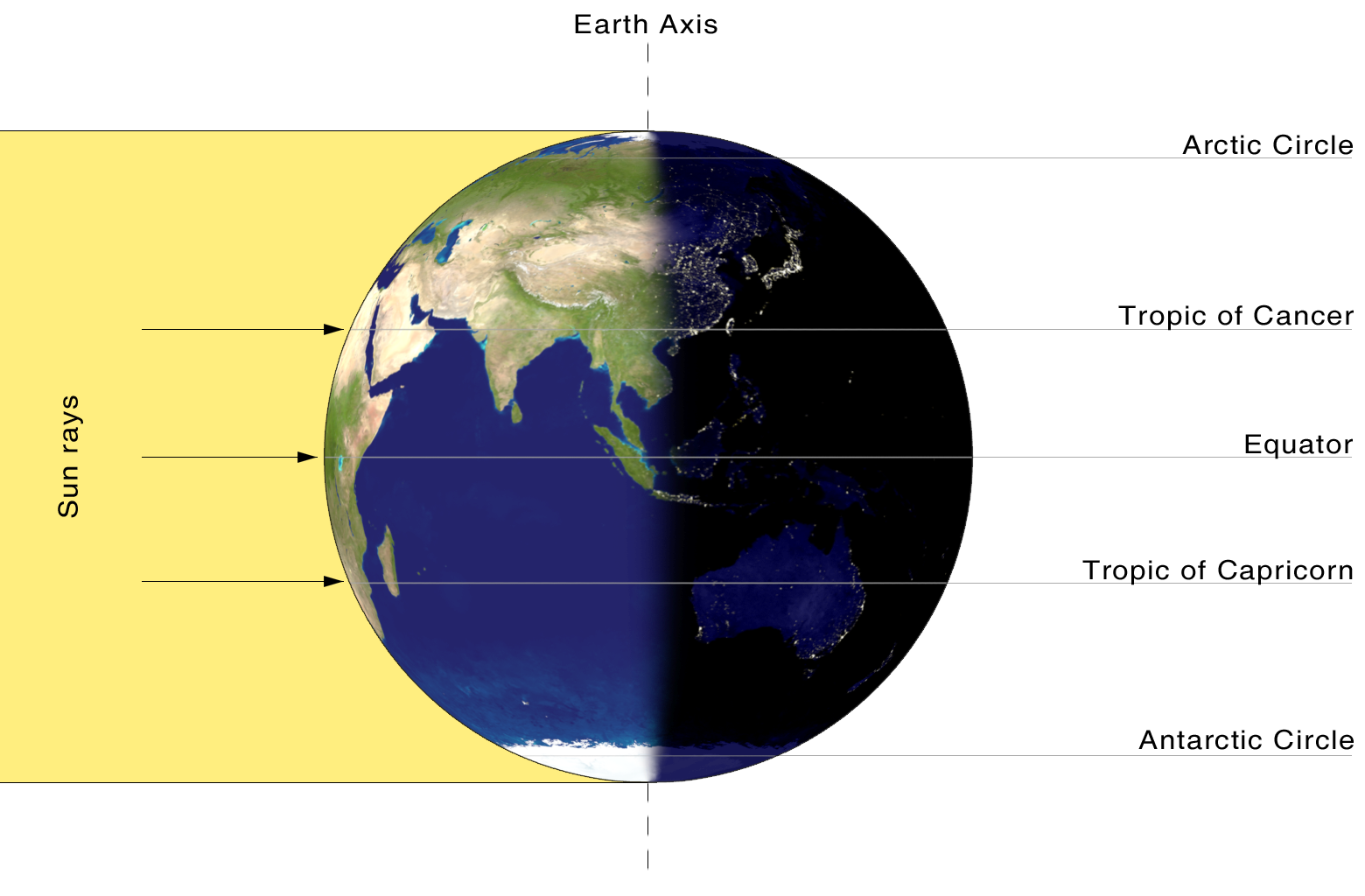

Vernal equinox and autumnal equinox. These names are direct derivatives of Latin (ver = spring, autumnus = autumn), and as such more apt to be found in writings. Although in principle they are subject to the same problem as the spring/autumn names, their use over the centuries has fixed them to the viewpoint of the northern hemisphere. As such the vernal equinox is the equinox where the Sun passes from south to north [across the equator], and is a zeropoint in some celestial coordinate systems. The name of the other equinox is used less often.

– Wikipedia:Equinox:Names

Links

Wikipedia: Equinox

I Love NY (State) Fall Foliage Report