I could probably talk about Amelanchier until my voice gave out (at least an hour!). It’s such a great multi-season plant in the garden, and brings so much value to wildlife, as well. It’s also a great example of how native plants convey a “sense of place” that is not imparted by conventional, non-native plants in the garden.

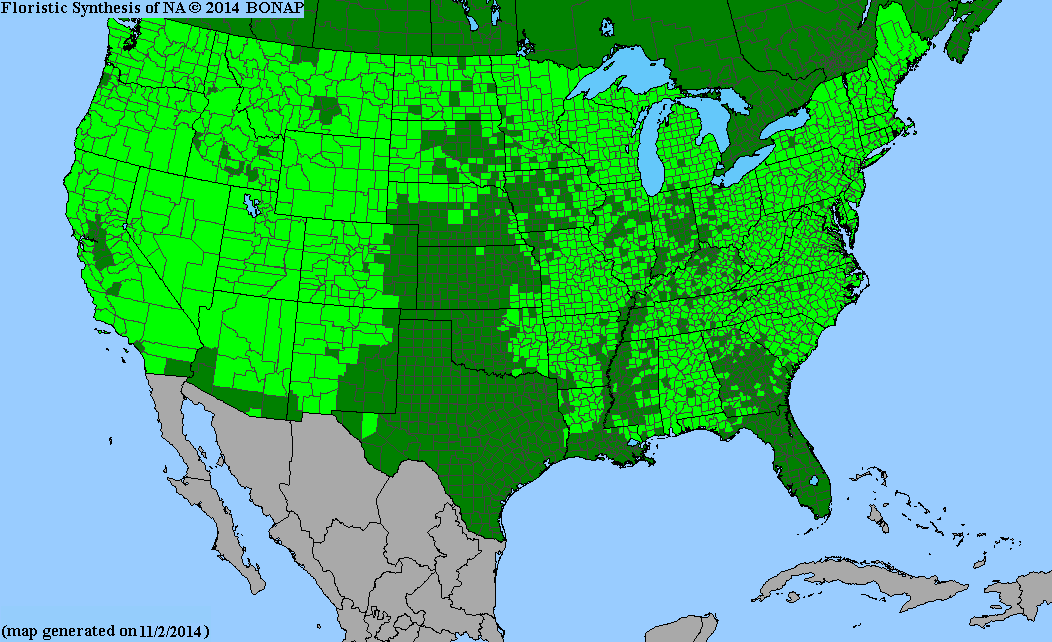

Although the Genus is distributed across the Northern hemisphere, the greatest diversity is found in North America. As you can see from the BONAP distribution map, Amelanchier diversity is the greatest in the Northeast. New York State hosts 14 species, varieties, natural hybrids, and subspecies. And New York City is home to 6 of those.

Amelanchier in my garden

Amelanchier was one of the key plants I included in my backyard native plant garden design in 2009. To fit my design, I needed a tree form with a single trunk and broad canopy.

Most of the species grow as multi-stemmed twiggy shrubs. In my design, I specified A. arborea, the only species that would normally grow with a single trunk. But straight species are difficult to find in the horticultural trade. Even nurseries specializing in native plants are unlikely to carry this species. I would likely need to find a “standard”: a plant grown with a single trunk that normally wouldn’t.

In Spring of 2010, I went hunting for a specimen for my garden. I found one at Chelsea Garden Center on Van Brunt Street in Red Hook, Brooklyn. It was the second most expensive single plant I’ve ever bought. But worth it!

What I found is Amelanchier x grandiflora ‘Autumn Brilliance’, a selection of a horticultural hybrid of two species: A. arborea and A. laevis. So arborea is in there somewhere! This cultivar was selected for its vividly colored autumn foliage. But any of the species will have beautiful fall color.

Their peak bloom in our area is just weeks away, before the ornamental cherries, and the dreaded callery pear. We’ll follow the seasons, starting with where we are right now, Winter.

Winter

This is Amelanchier ‘Autumn Brilliance’ in my backyard, as viewed from a bathroom window, after our January snowstorm.

Winter into Spring. Here’s a lengthening and expanding bud on my backyard Amelanchier, which I shared last week. It still looks like this. These terminal buds will become the flowers.

Bud break. The emerging inflorescence is covered in dense silvery hairs, which offer protection from late frosts. The leaves will emerge later from separate buds along the stems.

Spring

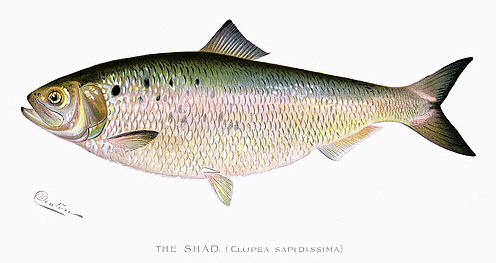

The big show is coming soon! It’s the first woody plant to bloom in my garden, early April or even late March in warm Springs. Two common names refer to its bloom time. Shadblow, because it would bloom when the shad are running. And serviceberry, because it bloomed when the ground had thawed enough to bury winter’s dead.

Over the next few weeks, these distinctive furry flower buds continue to expand.

As they mature, the inflorescences start to turn more upright and the pedicels lengthen. The whole tree turns a little less furry and fuzzy.

Finally, the buds start to open, revealing the bright creamy white of the petals. At this stage, they almost look like flowering peas.

When the flowers are fully open, they reveal their true nature. Amelanchier is in the Rosaceae, the rose family. Here you can clearly see the five-fold symmetry of rose relatives. At this stage, the leaves just start to emerge.

In full bloom they are spectacular and conspicuous in the landscape. This is when you are most likely to notice them, if you haven’t been stalking their progress all along, as I might do. Even at highway speeds, they are recognizable when flowering. There’s a line of them along the McDonald Avenue border of Green-Wood Cemetery. My commuter bus drove down this road on the return trip from Manhattan. I would sit on the right side of the bus to soak them in.

NYC is home to many bee species — especially mining bees, Andrenidae — that specialize in flowers of the Rosaceae. Most of our bees are solitary bees, and many of them nest in the ground. They are only active and visible for a month or so, as the females prepare new ground nests and provision their eggs with pollen balls. The rest of the year, the larvae and pupae are underground, slowly maturing, or aestivating through the winter, waiting for next year’s Spring.

Summer

Juneberry is descriptive: Berries ripen in the summer, typically June. Ripening berries on my backyard Amelanchier in 2011. They turn dark reddish purple when ripe, but good luck getting to them before the birds and squirrels. Technicaly edible, this cultivar’s fruit are mealy and seedy, better left for wildlife. Other species are used for making jams, or enjoyed right off the bush.

When we first bought our house, our next-door neighbors had an old, failing apple tree in their backyard, next to our shared fence. The fruit never ripened. Monk parakeets loved to munch on the apples.

They were also visited by cedar waxwings, another bird I had never seen before They seemed to love picking insects off the flowers in spring, presumably to feed to their young, as much as they enjoyed the fruits in summer. After our neighbors had their tree taken down, we rarely saw the monk parakeets, except when they flew overhead. And we never saw the waxwings again. I hoped another Rosaceae would bring them back.

This intent has been successful.

The berries are enjoyed by many different birds in my backyard.

Fall

Amelanchier‘s autumn foliage is brilliant, after all. This is from its second Fall in my garden, a year and a half after planting.

This is from November 2014, four years after planting.

Related Content

Twitter: #WildflowerHourNYC Twitter thread, 2022-03-09

Related blog posts:

- Woodland Garden Design Plant List, 2009-02-18

- Native Plant Profile: Amelanchier x grandiflora, 2010-05-08

Flickr, photo album: Planting a Tree

Links

Wikipedia: Amelanchier

BONAP North American Plant Atlas, county-level species Genus distribution maps: Amelanchier

MOBOT Plant Finder: Amelanchier

NC State University Plant Toolbox: Amelanchier

Plants for a Future

Pollen Specialist Bees of the Eastern United States, Jarrod Fowler