Note: I’ll continue to update this as I learn more.

Photo of Brood XIV Magicicada septendecim taken May 18, 2008 in West Virginia by Jason Scott Means

I just learned (from News12 Brooklyn) that the 17-year cicadas are about to return to Brooklyn. There have already been sightings on Long Island, in Otsego Park in Deer Park. There have also been sightings to the north of the city, along the Hudson Valley.

Magicicada is the genus of the 13- and 17- year periodical cicadas of eastern North America. These insects display a unique combination of long life cycles, periodicity, and mass emergences. They are sometimes called “seventeen-year locust”s, but they are not locusts.

– Magicicada, Wikipedia

13 and 17 are prime numbers. Evolution “discovered” prime numbers.

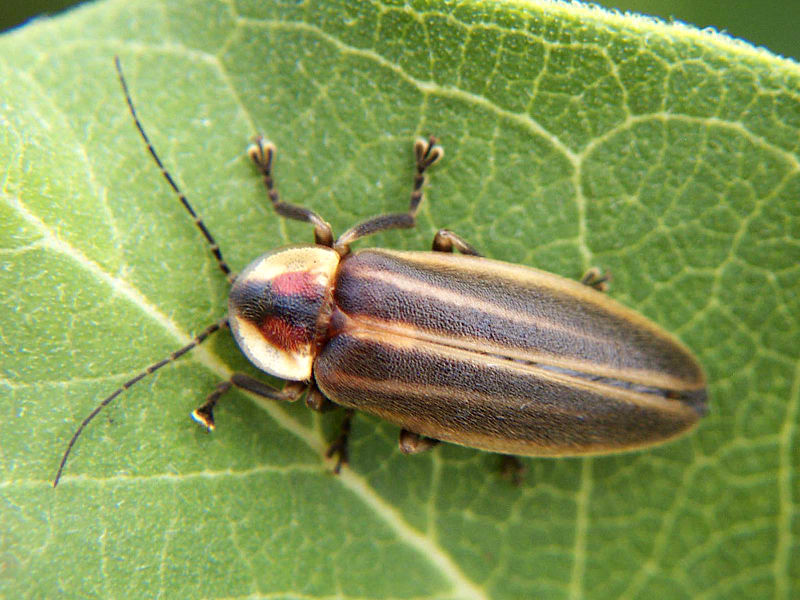

Periodical Cicadas appear earlier in the year than our regular, annual “dog-day” Cicadas, which don’t show up until later in the summer. If they are still here, we should begin to see signs of them now, certainly by the end of May. They can be readily distinguished by their red eyes (dog-day Cicadas have black or dark brown eyes), darker bodies, and smaller size. For comparison, here’s a photograph I took of a dog-day cicada, Tibicen canicularis, in my backyard last October.

Dog-day cicada – Tibicen canicularis, Flatbush, Brooklyn, October 2007

17 years ago, in 1991, I still lived in the East Village in Manhattan. We didn’t have them there. I didn’t move to Brooklyn until the next year, 1992, so I just missed the last cycle. They won’t be here again until 2025. I’m hoping – yes, hoping – that I’ll be in the thick of things here: detached houses, lots of open ground, and just a half-mile or so from Prospect Park.

Periodical cicadas are identified by broods categorizing the species, cycle, and years and range of a particular emergence:

In any given area, adult periodical cicadas emerge only once every 13 or 17 years, they are consistent in their life cycles, and populations (or “broods”) in different regions are not synchronized. Currently there are 7 recognized species, 12 distinct 17-year broods, and 3 distinct 13-year broods, along with 2 known extinct broods, found east of the Great Plains and south of the Great Lakes, to the Florida Panhandle.

– Magicicada Mapping Project

Brooklyn is part of Brood XIV (Brood 14), one of the 17-year broods. We can expect to see (and hear) any or all of the three 17-year species in Brood XIV:

Three 17-year cicada species exist, each with distinctive morphology (shape and color), behavior, and calling signals:

– Magicicada species, Magicicada Mapping Project

All three species are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as low risk, but near threatened, ie: close to being “promoted” to vulnerable species. Because they spend most of their lives underground, periodical cicadas are at risk from development which covers their routes to emergence at the surface. When they emerge, without sufficient woody plants – trees and shrubs – upon which to feed and lay their eggs, that generation will be irreversibly reduced for at least another 17 (or 13) years. Some broods are already extinct. Consider, for example, this observation from an unidentified entomologist:

Have you an ideal of the absolute in hopelessness? Well, let it be said that the house in which you live is comparatively new – built within 17 years. The ground on which ti stands was originally woodland. In the Summer of 1902 all the tree thereabouts were full of seventeen-year locusts. Eggs were deposited in the branches, the larvae came out, dropped lightly to the ground, and dug in. The long period of subterranean existence is almost ended. In the summer of this year the insects will start toward the light and air – and will come in contact with the concrete floor of your cellar! There may be another situation as hopeless, but certainly none more so.

– New York Times, June 23, 1919

You can help

If you see or hear periodical cicadas, you can report your observations online. The reporting page has photos so you know what to look for. Adult periodical cicadas are easily distinguished from our annual, “dog-day” cicadas by their red eyes, as shown in the lead photo above. The species pages, listed above, also have audio recordings so you know what to listen for.

[goo.gl]

Links

Brood XIV, Massachusetts Cicadas

magicicada.org

Cicada Central, University of Connecticut

Cicada Web Site, College of Mount St. Joseph, Cincinnati, OH

Chicago Cicadas

Magicicada, Wikipedia

Mathematicians explore cicada’s mysterious link with primes, Michael Stroh, Baltimore Sun, May 10, 2004

News

Hear that cicada chorus, taste that cicada crunch, Cape Cod Times, June 11, 2008

Cape is again abuzz, Boston Globe, June 10, 2008

New brood on its way to the top, Jennifer Smith, Newsday, June 8, 2008

Dogs rejoice, people duck: Cicadas are back, Columbus Dispatch, Ohio, June 7, 2008

City’s Giant Insect orgy, NY Post, June 5, 2008

After 17 years, cicadas ready to rumpus, Cape Cod Times, Massachusetts, May 31, 2008

It’s the year of the cicada, South Coast Today, Massachusetts, May 24, 2008

Noisy return of cicadas expected after 17 years, Jennifer Smith, Newsday, Long Island, May 22, 2008

Amorous singing cicadas grate on nerves, News & Record, Greensboro, North Carolina, May 20, 2008

Cicadas looking for love, Centre Daily Times, State College, Pennsylvania, May 19, 2008

Singing cicadas emerge in 13 states, USA Today, May 18, 2008

The cicadas are coming! The cicadas are coming … again!, Wilimington News Journal, Ohio, May 14, 2008

Cicadas coming to Clermont County, Community Press & Recorder, Kentucky, May 14, 2008

Coming Soon: The song of the cicada, New Albany Tribune, Indiana, May 10, 2008

The Kentucky Derby: Beware the Year of the Cicada, Minyanville, New York, May 2, 2008

Scientist awaits cicadas’ noisy return, UPI, April 25, 2008